DESTINATION RESTAURANTS

Destination Restaurants

by Sawako Kimijima

Seventy percent of the country is covered by forests and is surrounded by the sixth longest coastline in the world.

The country is long from north to south, has a wide variety of climates, and a rich diversity of flora and fauna.

The forefront of the restaurant scene has entered an era in which people can enjoy the creativity of chefs that can only be experienced in Japan's dense natural environment.

Each year, "Destination Restaurants" will select 10 restaurants to visit.

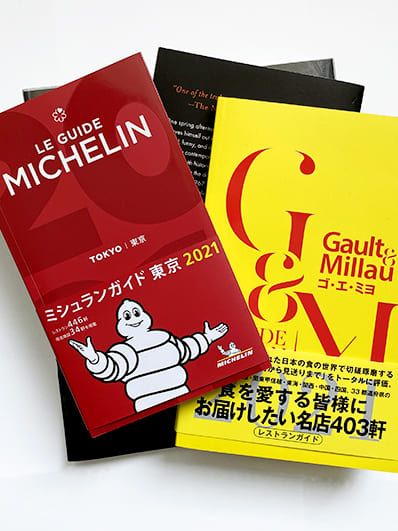

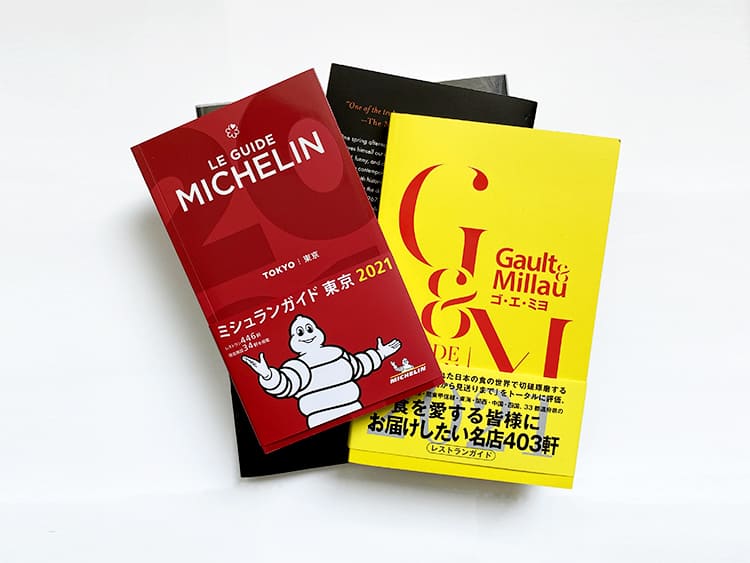

Destination Restaurants was conceived based on the idea of creating a recommended restaurant selection that only Japanese experts, for people around the world. Let us first look back briefly on the history of gourmet guides. In the 20th century, the Michelin Guide and the Gault & Millau, which debuted in 1900 and 1969, respectively, were the authoritative references. When internet use expanded at the start of the 21st century, guides using customer reviews and ratings became popular. Free from regional boundaries and cooking genres, such evaluations marked a shift in restaurant competition from the regional to global level.

Tokyo is among the elite when it comes to the number of Michelin-star venues, and thus Japanese restaurants tend to be regarded highly. However, as many of the evaluation bodies are outside Japan, factors that play a role in a restaurant’s offerings and the dining experience, such as climate, season, soil and terrain conditions — in short, fudo — as well as the subtleties of Japanese people’s spirit may not be fully taken into account.

Advancing cross-cultural understanding was a founding goal of The Japan Times, noted Minako Suematsu, the daily’s chairperson and publisher. “It was established [in 1897] with an aim to resolve the problem that English newspapers operating in Japan at the time, which reported on Japan from the viewpoint of foreign people, failed to help communicate the type of information the Japanese wanted the world to know.”

“In the same spirit, and at the base of this selection, there’s a desire to transmit to the world the authentic food culture of Japan that the Japanese want people to know about,” she added.

The restaurants were selected by a panel comprising Yoshiki Tsuji, Takefumi Hamada and Naoyuki Honda, all of whom are knowledgeable about restaurants both in Japan and abroad and, above all, cannot get enough of restaurant culture.

As part of the selection process, they made a bold decision to exclude Tokyo’s 23 wards and ordinance-designated major cities. The primary reason is that fudo can be found mainly in regions outside urban centers. Second, they wanted to turn a spotlight on talent who may otherwise remain unknown outside their respective local communities. Third, this would differentiate the list from existing ones, which tend to repeat destinations. “We’ve selected 10 restaurants that have not quite jelled yet, which we think is a positive aspect because they can develop further,” Hamada said.

A chef creates dishes that reflect a landscape. A restaurant is situated at the center of relations to nature and human activities, including the ecology of plants and animals, the terrain, soil, climate and seasons of the region, people’s creativity, and wisdom and skills passed down through generations.

According to Honda and Hamada, highly regarded restaurants in Europe tend not to be easy to access, often requiring hours of driving. But there is a reason for this. They typically use ingredients only available locally for an experience only they can offer. As a key example, Tsuji cited Michel Bras’ restaurant in France’s Auvergne region. “Bras’ is an omni-directional restaurant that has merged with Aubrac’s land,” he said. “It is a theater of the land, taking in its local landscape, flora, lifestyle and handicrafts.”

The three panelists agree that such restaurants have increased in number over the past few years in Japan. This is no doubt because chefs have taken their pursuits back to the sources of their dishes, including ingredients, production methods, soil and environment. They see their establishments as part of a cycle from production to consumption. Chefs who grow their own vegetables and rice, collect wild vegetables, fish, hunt and have their own vineyards are making their presence felt.

L’évo, which opened last December in the Toga area of Nanto, Toyama Prefecture, is a prime example, Honda said. The restaurant, built on the former site of a cluster of houses, overlooks the Toga River. The owner and chef, Eiji Taniguchi, built roads, laid water pipes, developed the fields, and constructed six structures for his project, including the restaurant, cottages and a sauna. The interior and tableware were designed by local artisans, and dishes and alcohol made from locally produced ingredients are served. Taniguchi’s venue and innovative fare are as impressive as the surroundings.

“The route to the restaurant is itself a story,” Tsuji said. “As you go deep into the mountains, feeling the fudo on which L’évo is based, past sake breweries and wineries, and potters that support Taniguchi’s creations, you can see flower buds of fuki plants along the mountain road where snow has started thawing,” Honda said. “I see only great things happening for a restaurant like L’évo, which has the attraction of the mountain setting, over the next decade.”

Hamada said one of his focuses is the role that restaurants will play in future society. Restaurants that can attract guests from around the world will clearly have a positive impact on regional economies. In addition, the creativity of chefs can stimulate and revitalize local fishing and farming industries. Japanese society is still not fully aware of the potential role that restaurants can play.

Takayoshi Yamaguchi, who runs the Mekumi sushiya in Nonoichi, Ishikawa Prefecture, travels every morning about 100 km to a fish market in Nanao on the Noto Peninsula for ingredients. He developed this route in search for a quality that would satisfy him, making purchases through direct communication with fishers. He completes the taste of his ingredients by further preparing and processing them. Yamaguchi’s approach has certainly raised the bar for sushi chefs.

Yotaro Sasaki of Tonoya Yo has operated the auberge in Tono, Iwate Prefecture, while tending fields and rice paddies and brewing doburoku unfiltered sake using rice he grows himself. The sophisticated taste of the sake, brewed using a method developed through trial and error, has enamored many, including Andoni Luis Aduriz, chef at the famous Mugaritz in Spain. Sasaki grows Tono No. 1 rice, a Japanese version of a heritage grain that precedes those introduced through cross- and selective breeding. His creation thus also preserves and passes down this rare rice variety.

Chefs see a landscape that may go unnoticed to diners, but which becomes apparent from the standpoint of using and creating. This is why an increasing number of them have made a point of getting closer to sites where ingredients they use are produced. Concerns about sustainability and food culture preservation make it likely that the trend of opening restaurants away from large cities will continue.

Hamada said one of his focuses is the role that restaurants will play in future society. Restaurants that can attract guests from around the world will clearly have a positive impact on regional economies. In addition, the creativity of chefs can stimulate and revitalize local fishing and farming industries. Japanese society is still not fully aware of the potential role that restaurants can play.

Takayoshi Yamaguchi, who runs the Mekumi sushiya in Nonoichi, Ishikawa Prefecture, travels every morning about 100 km to a fish market in Nanao on the Noto Peninsula for ingredients. He developed this route in search for a quality that would satisfy him, making purchases through direct communication with fishers. He completes the taste of his ingredients by further preparing and processing them. Yamaguchi’s approach has certainly raised the bar for sushi chefs.

Yotaro Sasaki of Tonoya Yo has operated the auberge in Tono, Iwate Prefecture, while tending fields and rice paddies and brewing doburoku unfiltered sake using rice he grows himself. The sophisticated taste of the sake, brewed using a method developed through trial and error, has enamored many, including Andoni Luis Aduriz, chef at the famous Mugaritz in Spain. Sasaki grows Tono No. 1 rice, a Japanese version of a heritage grain that precedes those introduced through cross- and selective breeding. His creation thus also preserves and passes down this rare rice variety.

Chefs see a landscape that may go unnoticed to diners, but which becomes apparent from the standpoint of using and creating. This is why an increasing number of them have made a point of getting closer to sites where ingredients they use are produced. Concerns about sustainability and food culture preservation make it likely that the trend of opening restaurants away from large cities will continue.

“We’ve entered an era where even restaurants in remote locations can establish their presence, thanks to social media,” Honda said. Such visibility is likely to shorten the time it takes for such venues to be discovered, allowing unique talent to be appreciated. “One of the aims of this selection is to support the efforts of the restaurants braving challenging locations,” Honda added.

The restaurants featured in this series are operated by chefs with a range of backgrounds, including those using techniques from the Edo Period (1603–1867), and specializing in various types of cuisine, from kaiseki Japanese traditional multicourse dinners to modern French and Italian. They also showcase the depth of the cooking culture that has developed over many years.

“I want not just overseas visitors but also more Japanese to visit these restaurants,” Hamada said. “Toward this, we should promote more flexible work styles that make it easier for people to take time off on weekdays.” The hope is both to introduce readers to restaurants beyond what they may have expected and to have a positive impact on the future of society.

Editor-in-chief, Cuisine Press Inc.

Kimijima founded in 2006 Ryori Tsushin (The Cuisine Press), a food magazine that reports on the latest trends of food scenes in Japan and abroad from a unique perspective (publication suspended after the final issue dated January 2021). Her web cooking media, The Cuisine Press, offers ideals of what food should essentially be, instead of just what is consumed from one era to another. Kimijima, who serves on the screening panel for the technician section of the “Culinary Expert Award: special category of Shizuo Tsuji Award of Gastronomy,” contributes columns to the “&Premium” magazine and “Axis,” a magazine on design, both published in Japanese. She has written a book in Japanese entitled, “Gaishoku 2.0” “Eating Out 2.0”, published by Asahi Press Inc.